I am blessed with having my birthday on the 31st December. This year’s event saw me not only seeing in a New Year, but the start of a new decade for me.

We also had a very generous offer from a good friend to babysit our brood so myself and my other half could go out to celebrate my landmark birthday, which resulted in very little productivity from me over the new year.

But get this; here in this part of West Wales we get a second go at seeing in the New Year and I get a second chance to write about it all! Result.

The New Calendar

The Calendar that we follow today is the Gregorian Calendar, with the new year starting on the 1st of January. It replaced its predecessor the Julian Calendar in the UK in 1752.

The Julian Calendar was the creation of Roman Emperor Julius Caesar in 45 AD, when he wanted to standardise the first Solar Calendars. The Julian Calendar’s formula had some miscalculations which eventually lead to the calendar falling out of sync with the seasons. Easter, traditionally observed on March the 21st was moving further away from the spring equinox with each passing century.

In 1582 Pope Gregory XIII introduced his own calendar to put right the miscalculations of the Julian Calendar. The Gregorian Calendar facilitated the realignment of dates with actual events like the Vernal equinox and Winter solstice. The Pope’s reformed Calendar was quickly adopted in Catholic countries such as Spain, Italy and Portugal. Other Protestant countries rejected the change because of its connections to the Catholic Church, fearing it was an attempt to restrict their religious activities. However, in 1700 Germany, a Protestant country, switched to the Gregorian Calendar. The United Kingdom held out until 1752, when the country went to bed on the 2nd of September and woke up on the 14th of September. At the time many ordinary people did not understand the changes to the calendar and thought they had lost 12 days of their life.

There are a few countries and communities who still observe the “Old” New Year which was celebrated on the 13th January. This includes a remote community in the Gwaun Valley, 4 miles from Fishguard, Pembrokeshire, who refused to move with the times. To this day they still celebrate their New Year, “Yr Hen Galan” on January 13th.

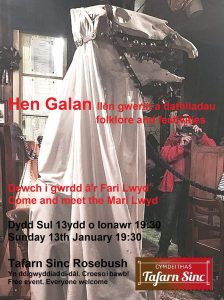

In the past, Yr Hen Galan was a bigger occasion for celebration than Christmas, celebrated with feasting and festivities. An accompaniment of these traditional celebrations was the appearance of Mari Llwyd (Grey Mare), where a horse’s skull is paraded on a pole with the bearer covered completely with a white sheet. The skull was decorated with seasonal trimmings such as greenery, ribbons and tinsel. The appearance of Mari Llwyd was not restricted to one day of the year, she was often brought out for midwinter celebrations stretching from the solstice to new year.

The earliest published account of Mari is found in J. Evans’ book “A tour through part of North Wales in the year 1798, and at other times”.

“A man on New Year’s day dressing himself in blankets and other trappings, with a factitious head like a horse, and a party attending him, knocking for admittance, this obtained, he runs about the room with an uncommon frightful noise which the party quit in real or pretend frights; they soon recover and by reciting a verse of some cowydd, or, in default pay a small gratitude, they gain admission.”

This quote is the earliest documented record of the activities of Mari Llwyd. Upon researching Mari, I have found many quotes declaring the antics of the Mari and her party as a “uniquely welsh ancient tradition”, although with the earliest documented evidence dating to only the early 19th Century claims that this is “ancient” are unconfirmed. There are examples of similar horse festivities and antics being carried out around the UK, however the “Mari Llwyd” is unique to Wales. With many local variations on the theme, for example, in the West country there is a tradition of the Hobby Horse (Obby ‘oss) riding and parading on May Day this too is thought to have roots in history to the days of Epona. Again, there is no evidence of this festival before the 18th century. Interestingly, the British aversion to eating horse meat is also thought to stem from the time of Worshipping Epona.

There are many theories on the exact origins of the Mari. Some claiming that the Mari stems from the times of the Celtic horse worship, one of the few Celtic deities to have been adopted by the Romans, Epona, the Goddess was a protector of horses, ponies and mules. Roman history portrays her and her horses as leaders of souls to the afterlife. There are also similarities with Rhiannon, a major character in the Mabinogion, a medieval welsh story collection who was often featured riding a grey horse. Something I personally found very interesting, was that Epona’s feast day in the Roman Calendar was given as December 18, which bearing in mind the issues with the calendars of the past, this is not far off the midwinter days on which the Mari likes to appear.

The theme that runs through all of the Mari antics are that the they are a form of visiting Wasailing, a luck bringing activity in which the participants accompany the Mari travelling from house to house (including the public ones!) singing and performing in the hope of being given a warm welcome and refreshments. With the ultimate goal being entry to the Big house where revellers would be set for a most fruitful welcome. To gain entry to the house, the Mari and her party would enter in to a poetic trade off called a “pwnco”. The householder and the Mari party traded rhymes until one side failed at their come back. If the householder lost, they let the Mari party in, if the householder won, then the Mari and her followers went away empty handed.

Midwinter was a hard time for those that worked the land an element of creativity surely brought them to perform such things as Carol Singing, Wassailing, Plough Monday and the Mari and her party. All of these activities offer some kind of performance in exchange for food, drink or money; in a time when it was illegal to beg. All of these activities would have been common place in our midwinter village communities, presumably more as an act of survival than a celebration.

Today many of these traditions are being revived as quests to explore an alternative lifestyle and an interest in our past is becoming ever more popular.

“Heb Enw Mari Lloyd” are a local group of Morris men and women based in Llanfalteg on the Pembrokeshire / Carmarthen border, who have worked to revive the traditions of the Mari Llwyd. My special thanks go to Caroline Yeates who very kindly gave up her time to meet with me and point me in the direction of resources for researching the Mari Llwyd. In addition, “trac”, an organisation dedicated to the developments of “folk” in Wales, utilise funding from the National Lottery and Arts Council Wales to fund project workers and workshops rolled out into Welsh Schools, to share the traditions, the dance and the music that go with the Mari Llwyd. Even going as far as to create a flat pack Mari Llwyd, which has proved useful where there has not been a real Mari available locally. In addition, a booklet by historian Rhiannon Ifans has also been published by the project.

For more information about the “trac” project please see https://resources.trac.wales/traditions/mari-lwyd

In the mean time, if you would like to get a second chance at celebrating New Year and meet a real Mari Llwyd, Heb Enw Mari Lloyd will be at Tafarn Sinc in Rosebush Sunday the 13th January to celebrate Yr Hen Galan https://www.tafarnsinc.cymru/eng/news-events.php for more information.